Roundtable discussion – Pseudorabies Awareness (Sept 2000)

ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION

Pseudorabies Awareness

With the pseudorabies eradication deadline quickly approaching, the National Pork Producer Council (NPPC) convened a panel of swine experts to discuss their experiences in handling the most recent PRV breaks as well as their recommendations on how practitioners can assist their clients in maintaining a PRV-free herd throughout the eradication process.

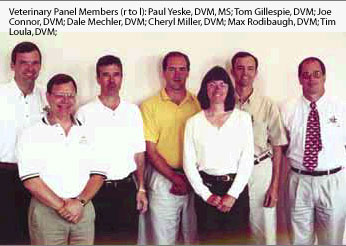

PY: Swine Vet Center, P.A., St. Peter, Minnesota; TG: Rensselaer Swine Services, Rensselaer, Indiana; CM: Regulatory Veterinarian, Indiana Board of Health; TL: Swine Vet Center, P.A., St. Peter, Minnesota; DM: Swine Health & Production, Algona, Iowa; MR: Swine Health Services, Frankfort, Indiana; JC: Carthage Veterinary Services Ltd., Carthage, Illinois.

How does a veterinarian/producer team go about implementing and maintaining an appropriate biosecurity plan to minimize the risk of PRV infection?

Dr. Yeske: We must first help our clients develop and implement a good biosecurity program. It must be a well-written plan so it can be communicated well to everyone within the farm and production system. The next item is to have a good isolation facility. That gives us a buffer between the original source farm and the herd farm that we’re going into. That also provides us the opportunity to retest the animals and make sure something hasn’t happened at the farm or there hasn’t been a problem in transport. Make sure we have good vet-to-vet communication with the original source farm so we not only understand the PRV status, but we also understand the other health statuses of the herds — both on the incoming gilts and semen of boars. Make sure we’re careful with dead animal disposal. Provide a set plan and pickup area for dead pigs.

Dr. Gillespie: I believe it is extremely important for the veterinarian to visit with every employee on the farm to assure that everybody is on the same page with the vaccine program and the biosecurity program. The person that’s running the power washer needs to understand that he may have one of the most important jobs. If everybody understands the risks and what we are trying to achieve, then I think we can more likely achieve our goal. Also, take a look at what other farms are doing around that particular farm. Look at biosecurity procedures, truck traffic, as well as the personnel practices.

Dr. Miller: As a regulatory veterinarian I am not on the farms as often as the local practitioner is. But what we can do as regulatory agencies is reinforce information that the local veterinarian is given through written communication with these farms on good biosecurity practices.

Dr. Loula: Assess your own farm — all confinement versus if you have outside pigs. You have higher risks with outside pigs. Also, assess the neighborhood. If there’s a high density of pigs, your risk is greater. Then external biosecurity programs become very important. You really have to do almost a neighborhood plan. That involves the veterinarian having local producer meetings. We videotape our producer meetings and make sure those not in attendance receive a copy. We are constantly putting PRV information and updates in our newsletters, to make everybody aware in an area, because of the lateral aerosol potential spread. Producers assume they have the best biosecurity program — showers and truck washes, etc., — but if you have a lot of neighbors with pseudorabies, you’re at risk.

Dr. Mechler: Making sure every pork producer is on the bandwagon to stop PRV is very important. We work closely with the regulatory veterinarians. We receive current maps of the positive sites and make a special effort to get them into our producers’ hands. It’s important that they know they are at risk. I think it’s important to blood test gilts in isolation and probably again prior to entry into the herd. I think it’s very important that we do a small statistical sample on all our units just to make sure things are going right. I’ve seen mysterious pseudorabies breaks and we think it may have happened with transportation or the use of a dirty truck, something like that. And I’d certainly want to catch that before they ever go into the sow unit.

Dr. Rodibaugh: Once you’ve established a biosecurity plan, make sure there is a regular process in place to audit it. With the breaks in the winter of 1997, we found out that many biosecurity steps were not being implemented. Having an auditing process in place might have prevented some of those breaks.

Dr. Connor: It helps a lot to have the farm staff actually come forward in a discussion of all of the movements in and out of the farm–movement of animals, supplies in and out of the farm, etc., (make that process interactive). They can lose sight of all of the movements in and out of the facility, whether it’s people, animals, supplies, feed or whatever. Allow them to discuss and say "this is how we’re going to manage each from a biosecurity standpoint." This process gets them farther along the trail of being able to fulfill an auditing program. These employees are the early warning signs of biosecurity short fall. As veterinarians we can’t be at the unit to provide ongoing auditing. We need to them to recognize when there’s a change in procedure or when there’s a change in movement and at least raise the question so it can be addressed.

Are there areas of biosecurity that are more critical than others when fighting PRV spread?

Dr. Loula: Transportation and new animal introduction have to be the top areas of biosecurity. Frequently producers focus on slaughter pig transport and they take other risks with light pig transporter or off-grade pig transport. As veterinarians we really need to re-emphasize that the risk can be quite high and more than offset the cost.

Dr. Mechler: We also need to reinforce with our producers that they don’t need to be sending pigs off the farm that can be vectors of contamination. This includes ruptured pigs that the sow barn guys want to keep alive and those poor-doing pigs they just want to keep alive and give to the neighbor down the road. I think those pigs are their biggest risk out there. We need to eliminate that practice and, if they are not a quality pig, euthanize them.

What are the economics of controlling and maintaining a PRV-free herd?

Dr. Loula: On the guy buying feeder pigs and finishing them, PRV doesn’t seem to be that big of an expense. He’ll see some respiratory problems and elevated health concerns and some death loss, but nothing major. The vaccine is 30-40 cents plus the labor to do it. In Iowa, for example, in the near future, if you have a PRV-positive you can only move those pigs directly to market. They have to be in sealed trucks and so you have to hire a veterinarian to come out and seal your truck. If you’re marketing on a four-barn finishing site, taking 180 out at a time, that’s multiple times you have to have a vet out to seal a truck, maybe over a 3-week period. On the sow end of it, it’s major cost. In Minnesota for example, we cannot move any positive pig except to slaughter. In an isowean type farm or a farrowing unit that moves off the 20-day-old pig, we can’t move it if that sow herd has four positives. Most of these farms wean twice a week. What do you do with your pigs? If you get four positives back on a 1000-sow herd, you can’t transport pigs for at least 3 days while the sows are being tested. You’ll have pigs all over the place. If the herd come back positive, you have to keep those pigs 30-60 days. In the worse case scenario where there is a high percentage of positives, the herd has to go to market and you have to slaughter the sows. Now you’re talking about 11 months before you can produce another pig off that farm. So it’s a huge expense on a sow herd. Practitioners need to keep preaching to the finishing guys that if you allow a lot of virus to be produced in this area, it can affect the entire operation.

Q: Any other cost factors, especially in these negative herds? Are there cost factors involved of not protecting?

Dr. Connor: I think the hassle factor is the biggest scare amongst the clients. Producers need to understand the financial consequences of going positive. Sealing trucks at 4:00 a.m. in the morning isn’t something they want to address.

Dr. Rodibaugh: A lot of producers don’t understand that if they go positive, they can’t bring a lot of pigs in to their systems. That limits the production system’s ability to utilize space properly as well as a lot of downtime on the system. Both place a huge financial drain on them.

What methods are practical to ensure PRV control?

Dr. Loula: Know your neighborhood and where the pigs come from. We often get lulled in to a false sense of security and assume all pigs are from PRV-free areas. That’s not always true. A lot of pigs are trucked from places that still have active PRV.

Dr. Mechler: I think we probably need to do a better job of blood testing sites on a regular basis to understand PRV (and other pathogen) status. I think it’s very important to make sure we have all the sites documented. Don’t assume just because it’s a new barn that it’s immune to PRV and other pathogens.

What about handling incoming stock in PRV-negative areas?

Dr. Mechler: Proper handling and acclimation of incoming stock is critical in controlling the area spread of PRV. You’ve got to have a program in place to handle gilts and boars. You have no way of knowing if the truck went through a highly contaminated area, wasn’t washed and disinfected prior to loading, etc., so you should not take any chances introducing those animals in to your negative herd until they are checked. We’re pretty aggressive because we’re in a little hotter area, so we actual blood-test them shortly after arrival and bank that blood in a freezer and then we’ll blood-test all gilts a week prior to entry into the herd. We hold all incoming animals at least 30-45 days before entering them in to the herd.

Dr. Gillespie: We are encouraging producers to vaccinate prior to shipment of naïve replacements into an infected area. Negative gilts are a good thing from a monitoring standpoint. But on the other side, you are putting the herd at risk if the naive animals become exposed and incubate the infection just prior to entering the herd.

Dr. Yeske: It’s critical that practitioners audit the isolation areas, too. In reviewing the isolation procedures make sure and ask how are the chores done on the weekend. Oftentimes during the week when the units have full staffs on farms, then protocols are pretty standard and pretty easy to follow, but sometimes, the weekends become a little different and so it’s important to make sure biosecurity has to work 7 days a week.

Dr. Loula: For example, our protocols for vaccine often say immediately vaccinate gilts upon arrival. To a practitioner that means the first day they arrive. A lot of producers interpret that to mean when they get around to it. If they’re not vaccinated and they don’t get it for 7-10 days plus the time it takes to build immunity, all of a sudden there are naïve animals for a couple of weeks in there and lot of potential problems.

Are PRV-negative herds still at risk for PRV?

Dr. Loula: Absolutely. We thought we were close to the end here in Minnesota and then we started breaking. What we have found is that as we get closer to our goals we start to relax on biosecurity, auditing, vaccinating, etc., and we open ourselves for breaks. And with so many naïve herds, the breaks move quickly and are devastating.

Dr. Connor: Illinois moved up a class December 31, 1999, but has had four positive cases in early 2000. So, you’ve got continual evidence that the risk remains high and will remain high until the last herd has the virus eliminated.

Dr. Rodibaugh: And we can’t underestimate the speed that the virus can move. We have to remember that as we get more negatives, we’re much more vulnerable than we ever were before and that just increases the speed of viral spread.

How do veterinarians keep producers focused on PRV countermeasures? What are some of the keys that practitioners can do to make sure there is a PRV awareness until this thing is gone?

Dr. Connor: I think every new break helps bring more attention to how easily this program can fall apart if not handled correctly. The real exciting thing is that the veterinarians and producers are working quite diligently on PRV eradication right now.

Dr. Yeske: Producers want to do the right thing. They want to make sure that they’re not causing a problem. I think producers have worked hard to make sure they’re being responsible along with making sure that everybody understands all the regulations. That’s difficult… the rules are changing. Producers don’t always understand the impact of those changes and it can be pretty devastating when it hits them. Practitioners need to make sure everybody understands the regulations and all the changes that are coming down the pipeline at them.

Dr. Connor: Besides keeping state and federal agencies aware of the costs of controlling PRV, I want us to make sure that there is funding in place for a quick response to PRV breaks. This is critical in reaching our control and elimination goals. We don’t want an issue such as who’s going to pay for the vaccine if a break occurs. You want all that prearranged so that the program can be implemented immediately. Delays become more critical as we move ahead.

Dr. Gillespie: Vaccine availability is absolutely essential. An awareness program is needed to get all practitioners knowledgeable about availability and push for funding in the states that need PRV vaccine.

Dr. Mechler: The other concern we’re facing in Iowa is vaccine availability. These flare-ups happen very quickly. They spread very quickly. You probably have a window of opportunity of about 1-2 weeks to get in there and get it stopped. We have to have the vaccine and funding in place to do this or we’re going to have major setbacks.

What are some of the factors that break down these biosecurity systems in PRV-negative herds?

Dr. Connor: Winter transportation causes a lot of PRV re-breaks. A system may have good vehicle wash and disinfectant techniques set up for the summer, but there are periods of time in the winter when they cannot adequately clean and disinfectant a truck between loads and allow a proper dry-down time.

Dr. Loula: Many producers assume that the truck they order is properly washed and disinfected. In the middle of a pseudorabies break of Minnesota, we audited a popular truck wash. The two-bay truck washers were washing PRV-positive loads right next to commercial market haulers and spraying all over each other. In February the wash was freezing and causing contaminated trucks. That’s not acceptable. As practitioners we need to audit these washes and assist wherever possible to assure clean trucks. We need to help our clients identify alternative washes that may not be on the beaten path. We also need to make sure our producers have alternate trucking routes to keep their pigs out of infected areas.

How do vaccines fit in today’s and tomorrow’s PRV elimination protocols?

Dr. Mechler: I think they’re the major line of defense. The vaccines work very well. I think we have to place them right. As practitioners, we need to know that the pigs don’t have maternal antibody interference because the sow herds are so hyper-immunized. I think it is critical that we look at maternal degradation studies on pigs and make sure our vaccine timing is right in the finisher group.

Dr. Rodibaugh: I don’t think there’s any way that we would have been able to eliminate virus without the vaccines. Even today we’re recommending that any producer in a high-risk area to continue to vaccinate pigs. We’re back to one pig vaccination, and certainly we’ll keep vaccinating sow herds as long as we can to clean up herds. I think vaccines will continue to play an important role. I hope regulatory officials don’t start restricting vaccines too quickly, because I think that could give us some severe PRV situations due to all of the naïve herds.

Dr. Miller: Producers need to be consistent with their vaccination programs. Once you develop these vaccine programs and they’re vaccinating in their finishers and breeding herds, practitioners need to stress the importance that it’s done on a consistent basis. Although we may see some seasonal fluctuations, I think we’ll start getting into problems when producers say, "we can back off the vaccine in the summer and then bump it up later." So I think they need to be very consistent with the vaccine to have the best offense that they can.

Are there any reasons for PRV-negative herds to maintain a PRV vaccination schedule?

Dr. Rodibaugh: You’ve got to evaluate that on a farm-by-farm basis. But in those high-risk states, high-risk areas, I think it’s fairly easy. The cost to eliminate the disease is going to be considerably higher than vaccination. Vaccination sure makes a lot of sense, especially in those high-risk areas.

Dr. Connor: I think the veterinarians have come to accept it. Pseudorabies vaccines are really the gold standard in terms of protection and increasing the challenge dose required for infection. The outbreaks in Minnesota and Indiana were quickly controlled via vaccination. As we move forward, I think what we have to do is also be certain that when the outbreaks occur, vaccine is quickly utilized in order to shut that new break down.

Is there a proven vaccination protocol when trying to fight PRV or maintain from breaking?

Dr. Loula: Our philosophy is to not let science get in the way of common sense. In the face of a break, we booster the whole sow herd again no matter what program they’re on. In endemic areas we’re doing quarterly vaccine. In areas of Minnesota which have had over 100 breaks in a 6-8 week period, we also intensified the piglet vaccination. We administer vaccine intranasally to piglets on the sow to try to protect pigs into the nursery. We go back into the nursery in 3-4 weeks and administered another intramuscular (IM) dose, and then, at about 12-13 weeks of age, or 3-4 weeks in the finisher, we administer a third dose.

Dr. Mechler: The key in Iowa is to vaccinate quickly and thoroughly. The intranasal vaccination on positive sow herds has been a tremendous tool for us.

Dr. Gillespie: A very important note is that we need to make sure the production system’s personnel understand that these vaccines are safe to handle. But we also need to make sure they know how to properly handle and administer the vaccines. Remind them that they are modified-live virus vaccines, and if not handled correctly, are totally ineffective. Make sure it is handled with a syringe that’s dedicated to pseudorabies vaccination. Also, don’t use any disinfectants to clean up the syringe just rinse the syringe in good hot water and let it air dry. Make sure we don’t mix up too much vaccine ahead of time. If we’re going to go out and do a lot of vaccinating, mix up about what you can use in a couple of hours so that you don’t let the vaccine start breaking down. And the vaccine doesn’t do any good if it’s in the refrigerator. Just because you own the vaccine, doesn’t mean it helps the pigs. It has to get in the pigs and we have to make sure we get good intramuscular injection as well.

Any benefits of intramuscular versus intranasal use of PRV vaccine?

Dr. Yeske: I think the intranasal vaccine is best used on the suckling piglets where we have the concern that maternal antibody blocking and it gives us an opportunity to have a different approach to the immune system. And so that’s where we’ve used the intranasal vaccine. Otherwise we’re using the intramuscular injections in the sow herds and in the nursery grow/finish animals because I think that gives us very effective control and is practical to get done. The only other time for intranasal that I could see is in an acute outbreak if you had an unvaccinated herd, it might be appropriate to doing the sow herd as well.

Dr. Gillespie: Intranasal route has benefit along with intramuscular dose to the sow herd in the initial outbreak. An intranasal dose to nursing piglets mimics the natural route of exposure and helps stimulate the initial immune response. The main route of course is the intramuscular administration of vaccine. Combination products are very beneficial in vaccinating the adult animals. One or two IM doses can be used in the grow-finish animals, depending on the need.

How do we keep our clients from getting complacent about PRV biosecurity and vaccination?

Dr. Connor: Complacency generally doesn’t occur in the hot areas. As veterinarians we need to continue to push the urgency of PRV management and information transfer.

Dr. Yeske: One of the things we did as we got into some of these hot pockets was gather all the area veterinary practices in one place and discuss the issues, regulations, and information. We were all on the same page. One of the best things that came out of this type of meeting was an email program that allowed us to email out all the positive herds everyday so people could know as soon as possible when the status was changing. Maintaining a high level of communication really helps us get on top of the break alot more effectively.

Dr. Gillespie: It’s extremely tough to keep the PRV awareness issue in front of producers in states that have maintained a PRV-free status for a period of time. But we know outbreaks occur in the winter, so can we make a conscious effort to remind people that winter is coming and to stay focused on PRV protocols.

Do you have much problem convincing PRV-free herds to maintain a vaccination program?

Dr. Yeske: Well, it’s difficult in the finishers. People had a harder time in justifying that cost. People are more are willing to go ahead and get that vaccination done just because they’ve seen it happen in areas that they expected to be free. And so, today it’s a much easier sell, but unfortunately a lot of people had to experience some problems first before we got there.

Dr. Gillespie: For the state of Indiana, we detect a very relaxed attitude today towards the pseudorabies eradication program because most producers now tend to look at it as being behind us. We had the problems in 1997. It was in front of the producers a lot at that point. Everybody was on the same page. I think it’s important for veterinarians to try to assess concentration points of pigs, look at the producers around these points and encourage them to continue to use vaccinations. The vaccines are very, very good. They have been very helpful.

Is there a time where PRV vaccination is a little bit more important than other times?

Dr. Loula: We’ve definitely had more trouble in the winter seasons than the summer seasons. The temperature’s probably right to sustain virus more in the winter months or the 7 or 8 months of that we have colder temperatures. But, that threat doesn’t disappear in the summer, either.

Dr. Yeske: I think the one thing that the experience in southern Minnesota taught us was that you can’t predict when it’s going to blow up. That’s why it’s so important we continue to keep these herds vaccinated because you’ll be surprised how quickly things can blow up. It also showed us how quickly pigs move within an area and how far those connections can extend. That’s one of the things that’s changed in our industry. It’s changed for the good. Multiple-site production has allowed us to move very quickly in cleaning these herds up and we’re able to jump into these herds and make rapid progress and cleanup that we might not have been able to do before. And with the more movement, pigs can come from many different areas and it can happen at a very fast pace. And as we get closer to eliminating this disease, we have to deal with a greater number of naïve pigs. That means we also have a greater risk. That’s probably the most important take-home message — every day we become at greater risk and vaccination is still probably the single most important thing we can do in protecting the herd.

What have we learned from these recent PRV breaks?

Dr. Yeske: Don’t let up on the vaccination and make sure that you keep current on your vaccination program. The risk is just too high and with the rules and regulations in place on animal movement, those restrictions are going to be too difficult to live with. We have to be very proactive and that’s the best proactive measure that any producer can make is to make sure their herds are protected with the vaccine.

Dr. Rodibaugh: The Indiana breaks taught us that it was a lot easier to blame somebody else for our problems than to look at our internal risks. We had places that were blaming the neighbors or blaming pig movement, when in fact, they were going to the slaughter plants and not changing boots and not washing trucks. It opened my eyes to the importance of biosecurity 24 hours a day.

How can practitioners do to help prevent these costly PRV flare-ups?

Dr. Loula: We can’t let up on our communications efforts. We’ve got to have the state and federal agencies as well as local practitioners and the NPPC organizations keeping this in front of producers as much as possible. We can’t let up until we’ve cleared up the last herd. At this stage of the program, monitoring is vital to our understanding, what statuses are in areas, individual farms, different locations, and so forth.

Dr. Mechler: We as practitioners need to make PRV our witchhunt. We have to always be searching for it, even in areas we know it hasn’t been in a while.

Dr. Yeske: Practitioners and producers need continue to keep pressure on the state and federal regulators to make sure that there’s adequate funding available to keep the program going. We don’t want to stop short. We want to finish the program. I think producers have cooperated extremely well to get this job done, along with the veterinarians, and we want to go ahead and finish it. We have to keep the momentum going and so, we have to keep that pressure there as well so that we don’t stop short of the goal. I think making sure we keep in contact with our local board of animal health and making sure they understand its impact on the state and your clients. Practitioners need to take a more active role and make the time to get this done.

Dr. Loula: We called the local practitioner meetings and encouraged local producer meetings. We got on the phone and we told all our eight vets to call everybody they were working with. We got the board of animal health to get on the radio in those local areas. We got in the local newspapers about pseudorabies outbreak. I think you use every bit of media that you can to get everybody informed. Use all levels of communication and get everybody talking about it.

In the areas that you’ve had these breaks, how quickly and what type of protocol did you approach with the vaccine?

Dr. Mechler: First and foremost vaccinate. Get all the herds in the area vaccinated and get everybody current on their vaccinations. Then you can start doing the circle testing, the epidemiological studies to find out what happened, what went wrong. Don’t try and figure out what went wrong first. Get it stopped, then go back and try and trace the steps. But the most important thing is get it stopped first.

Dr. Connor: The real importance there is the early detection, circle testing, and immediate use of vaccine in that circle.

Dr. Yeske: I actually believe strongly that we approach PRV breaks backwards too often. We oftentimes want to find out what is going on and do lots of testing. That was a mistake we made early on in Indiana. We didn’t get the vaccine in quick enough. We need to stress upon our colleagues that as soon as you find out a herd is clinical, then vaccinate. Then separate or maybe divide those herds up into the ones that are clinical or the ones who already detect a seropositive animal and maybe you would handle those differently. But there’s no doubt in my mind on an active clinical break, use vaccine the next day. You can always come in and circle test.

Dr. Loula: I’m kind of making the call on when to drop back on vaccines. But like the instance in Minnesota that we had couple of months ago in a county that had been adversely free for almost 5 years of pseudorabies — but only a county or two away from some of the hotbeds of pseudorabies. They had a very high proportion of nonvaccinated finishing pigs. Experience has quickly taught us we’re going to have to take Iowa, southern Minnesota, and parts of Indiana and vaccinate the finishing pig populations. It’s too costly to stop right now.